Encyclopedia | Library | Reference | Teaching | General | Links | About ORB | HOME

History of

medieval Norwich

History of

medieval Norwich

| Effects of the Conquest |

| Construction of castle and cathedral |

Many burgesses were displaced when their houses were torn down to make room for the castle and its fee, in a central location in the borough. The castle was in existence by 1075 and may have been built within a year of William the Conqueror's victory over King Harold Godwinson – if, as seems likely, the "Guenta" where William FitzOsbern built a castle from which to take charge of the northern half of the kingdom (in the Conqueror's absence abroad) may be identified with Norwich. Its site chosen for height and for proximity to the crossroads and fords/bridges, the purpose of the castle was not so much to protect as to control the inhabitants of a town where the Conqueror's principal enemies (the Godwinsons) had held influence. An original wooden structure would have been replaced by the present stone keep within a few decades.

Norwich castle keep

viewed from the far side of the (Mancroft) marketplace

still appears to impose authority over this part of the town

as it must have done eight hundred years ago.

photo © S. Alsford

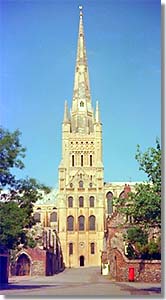

Norwich cathedral tower and spire

viewed from within the Close, looking northwards to

the south face. The cathedral took almost two hundred

years to complete; the unusually high spire was built at

the close of the Middle Ages to replace an earlier one.

photo © S. Alsford

| New settlers and their influence on Norwich |

An alternative marketplace had already presented itself, before 1086, in the French quarter established by Earl Ralph on the west side of the castle, just beyond the Great Cockey. This foundation had "new town" status and was part of a broader Norman policy of deliberate colonization of Anglo-Saxon centres (although the establishment of a separate but adjacent Norman quarter was itself rare). Yet we should not ignore the need to relocate existing residents displaced by the castle. This new town is later found with the name of Man(nes)croft, recalling the large open area around which the settlers spread and on which a parish church was built by the earl; this open area was likely (perhaps consequently) used for trading. The name of this area implies that it had once served as common fields of the townsmen, and it was perhaps a shortened form of "portmanscroft"; however, recent excavations have revealed that there was some Late Saxon settlement there. It is significant that the original main access to the castle fee was on the Mancroft side – in the opposite direction to the old borough centre. Some of the land in Mancroft was held by Norman soldiers, while there is evidence of a number of houses in other parts of the town held custom-free by men associated with the castle-guard (e.g. crossbowmen, watchment). After Ralph's rebellion, the number of French burgesses increased from 36 to 125, while the Anglo-Saxon population decreased. Although we cannot dissociate the foundation, within a decade of the Conquest, with the building of the castle, Mancroft was more than an outer garrison for the castle. It must have been intended as a mechanism for provisioning for the castle and the type of settlers sought were merchants and tradesmen. Mancroft was made a borough in its own right, as its original name "Newport" indicates, with customary dues kept down to 1d. a head, to attract traders. It may well have had its own reeve and court. Its market, with a monopoly on castle business, gradually superseded Tombland and became the focus of the city. The Tolbooth established there to collect market dues would have been a preferable choice for the administration of justice to the open-air Tombland. When the rival Norman and Anglo-Saxon boroughs amalgamated into a single administration, we cannot say. Certainly we have the impression of a unified community when Norwich received its first royal charter of liberties in 1194, although there is some evidence that the new local administration (now to be chosen by the burgesses, rather than by the king) involved two or more reeves, with Normans and Anglo-Saxons sharing power. However, by this time the cultural difference had dulled. Commercial intercourse, common ambitions (such as self-government), and common hatreds (such as against the Jews), helped forge Norman and Saxon into one community. Despite Mancroft's rise and Conesford's decline, the character of the borough owed as much, if not more, to Anglo-Saxon than to Norman culture. A study of the customary laws of the borough shows little indisputable influence of French legal precedents. The burgesses resisted Norman innovations such as trial by combat or ordeal, or murdrum (a fine for an unsolved murder), obtaining exemptions from these in their first charter. The Anglo-Saxon preference for compurgation, as proof of guilt or innocence, persisted and only gradually gave way to trial by jury. That assizes of mort d'ancestor and novel disseisin were inoperative in towns was, however, a reflection more of the essentially mercantile interests of burgesses, rather than a cultural matter. And the abolition of the Anglo-Saxon miskenning (invalidation of a case in which pleading was not carried out according to strict formula) shows that the burgesses were not averse to discarding old custom when it hampered them. On the other hand, there were some important consequences to Norwich from the Norman Conquest. The local authority of the sheriff (a king's man) was enhanced at the expense of the earl, particularly by making him constable of the castle. It was aversion to his government, in part, that motivated the burgesses to seek self-rule. More important was the stimulus the effects of the Conquest gave to trade, although these did were not fully realized until the twelfth century, and Anglo-Saxon and Norman had equal roles in this. Nor must we ignore the less direct stimulus of the settlement of Jews in English boroughs, mainly from the time of William Rufus on (although an Isaac was living in Mancroft in 1086). Norwich was probably one of the earlier destinations of Jewish settlers – who came principally from northern France and the Rhineland – being a county town with a royal castle. A Jewish community there is evidenced in the mid-twelfth century chronicle of Thomas of Monmouth; the building of a synagogue in the reign of Henry II furthered the development of a Jewish quarter in Norwich. It was located at the castle entrance, on the route leading thence to the market. This placement gave it immediate access to the protection offered by the king (whose chattels the Jews were in law) and proximity to the place of business. Their principal business was money-lending, most others being closed to them. They had no role in city government, not being given citizenship (which involved the taking of Christian oaths), and this in turn disadvantaged them in commercial activities. Nor was membership in craft gilds open to them, again because of the religious aspects. On the other hand, Christian dictates made Jews the source of the necessary financial backing for commercial ventures; if they charged a high price for this service, it was because of the risks from unpaid debts and absorption of much of their profits by the king (in the form of heavy fines). The Abbey of St. Edmunds and the sheriff of Norfolk (William de Caineto) were among heavy debtors to Norwich Jews in time of Henry II. Resentment at this state of indebtedness, combined with the burgess' instinctive antipathy towards any newcomer, fuelled by religious tension, resulted in aggression. The massacre of Jews in 1190, in Norwich as elsewhere, was in part "a new way to pay old debts", by getting rid of creditors. It was in fact at Norwich that the first accusation of ritual murder of a Christian by Jews was used as an excuse for hostility, and where a burgess community first meditated wholesale massacre of Jews (1144). Thanks largely to the protection of king, sheriff and castle, the Jewish community prospered in the face of adversity, such as:

St. Peter Mancroft

built by the earl to serve his new borough as

parish church; rebuilt on a magnificent scale

in the first half of the 15th century by the city's

merchants in gratitude for their prosperity. The

western tower, illuminated at night, illustrates

the imposing scale (note the castle in the background).

photo © S. Alsford

| The fee farm |

It was this prosperity that gave the citizens the resources to acquire a certain measure of administrative independence. In 1065 the king was the principal, but not the only, lord of Norwich. The private sokes of Stigand and Harold, however, gradually disappeared when cathedral, castle and Mancroft were raised on the sites of the sokes. The king still shared his lordship with the earl, who took the "third penny" of all dues until at least 1191; but that was probably his only surviving right in the borough, the sheriff having absorbed the earl's administrative duties. One of those chief duties was the collection of royal revenues from the boroughs. A popular method of doing this was to "farm" it: to negotiate a lump sum to be paid at the Exchequer in London. If revenues failed to meet the sum in any year, the sheriff had to make up the difference from his own purse. Naturally, he attempted the reverse: to collect more revenues than the negotiated sum, so that he could keep the surplus. Since large sums were often paid for shrieval office, we may guess that the profit was good, and there is evidence of various types of extortion. Often the sheriff made his profit by sub-leasing his farming rights to other individuals. The burgesses were anxious to rid themselves of this drain on their income, by taking the farm into their own hands. Yet Norwich did not achieve this until 1194, although the burgesses were wealthy enough to have together afforded the money gift necessary to persuade the king to grant them the farm. Perhaps the Anglo-Saxon and Norman communities were still too much at odds to work in unison. More likely it was simply a case that Henry II, fearing that to give the boroughs too much power over their own affairs might lead to emulation of the continental communes, only experimented with grants of the farm to boroughs; his charter granted to Norwich circa 1158 went no further than recognizing unspecified local customs that the citizens claimed to be theirs by tradition. His sons Richard and John, on the other hand, had more pressing needs for money and were more amenable to selling to towns the privileges they wanted. The burgesses paid 200 marks for taking the farm out of the hands of the sheriff (this in addition to the actual amount of the farm itself, which was £108). Historians have debated whether grant of fee farm automatically involved the right of the burgesses to elect their own officer to take responsibility for collecting the farm and accounting for it at the Exchequer. In Norwich's case, the 1194 charter clearly makes the association: after confirming to the citizens all their traditional liberties, in return for render to the king of the fee farm, by the hand of the prepositus (literally the "foremost" member of the community, usually translated as "reeve" or "bailiff"), the charter continues that the citizens may elect annually their own reeves (with the proviso that those elected be acceptable to the king). This represents the beginning of self-government in Norwich.

previous |

main menu |

next |

| Created: August 29, 1998. Last update: February 28, 2001 | © Stephen Alsford, 1998-2003 |

|

Encyclopedia | Library | Reference | Teaching | General | Links | Search | About ORB | HOME The contents of ORB are copyright © 2003 Kathryn M. Talarico except as otherwise indicated herein. |